My Trust Issues with Trust by Hernan Diaz

The reality-warping forces of wealth, narrative, and criticism

Trust is the story of an early twentieth-century Wall Street tycoon and his wife told in four unreliable narratives that add up to what book marketers are calling a “literary mystery.” This mystery is, I think, the only reason why I finished the book — that and the white space galore.

Diaz writes with the practiced fluidity of one who writes a lot — by day, he’s an academician. The best of the four parts is the first, an upclose yet at the same time curiously removed story of the couple, Benjamin and Helen Rask, in which Diaz boldly “goes there” showing the horrors of early psychiatry in unflinching detail.

The second part of Trust contains someone’s heavily spaced notes for an autobiography, and it reads like it — it can’t even be called writing but scraps of proto-writing (ah yes, “notes”). The effect is so jarring that some readers, complaining of receiving incomplete drafts, returned their copies of the book.

Aside from the part two fiasco, Diaz is at his best when he takes risks. The other successful part of the book doesn’t occur until its final pages when Diaz takes on the ultra-close first person voice of a woman. Regardless of what the cultural age tells us about the propriety of an artist inhabiting the persona of another human being from a marginalized group (we all know how important propriety is to artists), it’s always an impressive technical feat for a writer to take on the voice of the opposite sex convincingly.

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for the third part of the book in which the author inhabits the character of a supposedly renowned female writer for The New Yorker — a voice that feels completely made up.

This contrived quality is the problem I have with a lot of contemporary fiction. As I mentioned, Diaz hails from academia, where he’s a professor of comparative literature, and the way he approaches the book feels more like an assignment in which the author follows a prompt. Instead of drawing from the River of Aesthetics, he uses a lesser form of imagination.

As a professional copywriter, I’m well-acquainted with this baser imagination. It’s particularly useful in selling things. Unlike the River of Aesthetics, one employs it calculatingly using one’s analytic faculties. Let’s take, for instance, the act of writing a commercial. At the start of a project, one receives a document known as a creative brief. Prepared by a marketer, it often summarizes the objectives, audience demographics, brand positioning, value proposition, user benefits, messaging, and tone. A brand architecture may also be supplied. (It’s uncanny how many brands boast “human,” “empathetic,” and “expert” among their pillars these days. While humans evolve into brands, brands seek desperately to turn themselves into humans.) Thus before setting down to write, one is aware of exactly what one is selling — the product or service as well as the brand — and how. With the content thus mapped out, one then gets “creative,” drawing from the aesthetic mind, but only insofar as it can package the message in a way that’s appealing to viewers, not unlike how a baker decorates a cake. Consumers, being human, are attracted to aesthetic things.

When working with this form of the imagination, there’s a constipatory feeling of forcing out the aesthetics elements. It is an inelegant process, but the practiced copywriter is skilled at making the creative product feel spontaneous. It’s a wonderful way to make money for other people, and oneself, and when not jaded, one can take satisfaction in connecting people with solutions that solve their problems. It may be artful, but it is not, however, art.

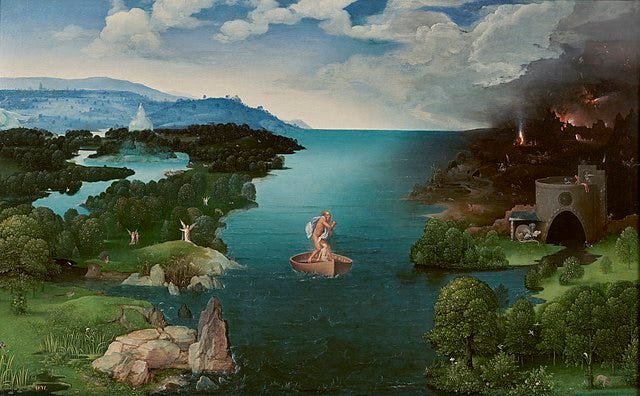

On the other hand, sitting down to write art rather than — the dreaded word — content, is a more mystic process. The collective aesthetic consciousness may perhaps manifest itself in various user interfaces — I’ve heard it elsewhere described as a cave — but at least one other artist I’ve traded notes with agrees that a river aptly describes the interminable channel of images that rushes past when this imagination is activated.

There’s a spirit of discovery and spontaneity when fishing out of the River of Aesthetics. You never know what sparkling, trembling specimen you’ll scoop out, but you can be sure as it flops with life of its own that it has the unquestionable quality of Truth, of always having existed, if only in this parallel world. So even though what you draw from the River may be totally made up, it is never contrived. Sometimes, it’s more convincing than anything drawn from real life, or it combines with raw material so authentically as to render real life more credible than it would otherwise stand on its own. Flaubert plucked Madame Bovary from this river, James Joyce rescued Leopold Bloom, Mark Twain dragged out Huckleberry Finn.

It’s unfair for me to presume to know Diaz’s process, but it’s also beside the point — it’s much more fun to write an essay on aesthetics than pan a book. Perhaps Diaz happily drank from the waters of the collective unconscious, and it’s the execution itself that leaves one wanting. But either way, the book reads as if the author conscientiously undertook to write a woman-behind-the-man story that puns on the word “trust” and explores the reality-warping power of money and narrative as an assignment.

“My job is about being right. Always,” Benjamin Rask says. “If I’m ever wrong, I must make use of all my means and resources to bend and align reality according to my mistake so that it ceases to be a mistake.”

Indeed, one can sense the way Diaz effortfully bends and aligns the narrative to support his thesis in the way a creative team painstakingly brainstorms the direction of ad creative with sticky notes on a whiteboard.

In the same way that Mrs. Rask’s personhood has been wiped out of history — purposely, the text seems to suggest — by her husband, and her story is appropriated (the text seems to suggest) by a male writer whose novel comprises part one of Trust, Mr. Rask is rendered one-dimensional by Diaz while his wife’s character is rounded out thanks to the diligence of a virtuous female writer in part three. In this purported exploration of the inherent unreliability of narrative texts, the author’s own credibility is questionable. In the end, it is Mr. Rask who is left without a voice and whose story remains untold, or at least the story we’re presented with can’t be … wait for it … trusted. Diaz seems to cast judgment on Rask, condemning him for his wealth and his privilege as well as his philistine taste in music and inability to appreciate his wife’s fine mind. If I didn’t think there was an element of evil in bad taste, I wouldn’t be writing this Substack, but even I wouldn’t go so far as to equate artistic taste with moral virtue in the way the author does here.

But before I pretend like this is a review rather than an exploration of what I hate about so much fiction, I’ll stop myself from going any further in warping the reality of this book to conform to my own thesis — the foundation of which, after all, rests on an enchanted river of Truth no one has ever seen with their eyes.