The Gulag Archipelago Turns 50: My Thoughts on Volume 1

When life gives you Lenins, turn them into the greatest nonfiction book of the twentieth century

Seeking to document not only Solzhenitsyn’s own imprisonment but the staggering machinery of the Soviet prison camp system itself — including, in just the first volume alone, the legal codes, arrests, interrogations, court system and “trials,” transport system, and camp conditions — The Gulag Archipelago is so expansive in its vision and examines an epoch so expansive in its horrors, it’s a wonder that it only took 2,264 pages and three volumes to fulfill its undertaking. It’s also a wonder that it’s one of the most entertaining books I’ve read — at least I can say this now about volume one.

Subtitled “An Experiment in Literary Investigation,” the book compiles interviews with former prisoners, historical documents, diaries, and Solzhenitsyn’s own experiences into a blend of history, memoir, philosophy, and prison literature amounting to a tragicomic epic that is as sweepingly broad as it is minutely personal.

But it’s not just the form that’s experimental, it’s the telling itself — The Gulag Archipelago isn’t so much a history as it is a harangue, a scathing and yet hilarious account by someone who experienced its horrors firsthand. (Solzhenitsyn served 11 years for criticizing Stalin in a private letter to a friend.)

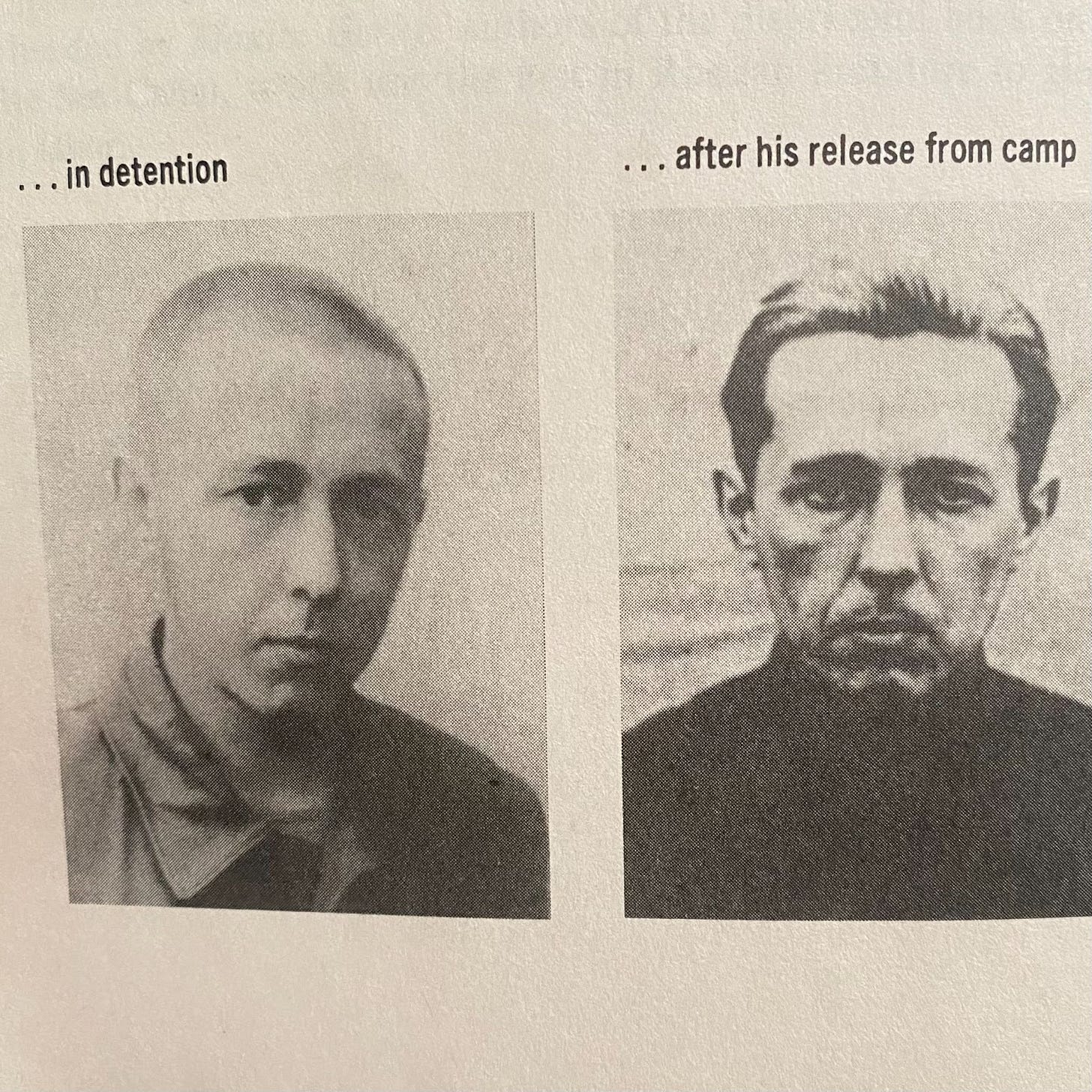

Like Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy, which was written as its author awaited his execution, The Gulag Archipelago is the sort of thing you write when shit gets real, the purest distillation of human truth. Solzhenitsyn has descended into the lowest depths of human misery, stripped himself of all earthly desires and attachments like some tortured and abused Buddha, and achieved dystopian Nirvana.

“I am the interstellar wanderer!” he declares after his transformation from haughty, Party-line-towing soldier into wise ascetic. “They have tightly bound my body, but my soul is beyond their power.”

Unlike Boethius’s treatise on religious philosophy, TGA is understandably lacking in Boethius’s optimism. Still, it takes up subjects of no less spiritual import — the human capacity for evil and how a society succumbs to it — and with a higher JPM than you could ever hope for in a 700+ page history.

I’ve compared TGA before to the 2017 satire Death of Stalin, a recent favorite of mine. Scenes of comedy abound: An escapee forgets his fake identity name and so pretends to be asleep during the train roll call until he’s the last man called, a standing ovation in praise of Stalin goes on interminably because no one wants to be the poor fool to be arrested for sitting down first. And then there are the one-liners — such as when a prisoner receives a 25-year sentence:

The chief of the convoy guard was curious: "What did you get it for?"

"For nothing at all."

"You're lying. The sentence for nothing at all is ten years."

After all, how could the apparatus of the gulag system be portrayed as anything other than a giant farce? There’s much chatter these days about how we’ve entered a simulacrum. If that’s true, the USSR entered it well before we did when Soviet life took on a grimness of such grandeur that it became a satire in itself.

But while The Gulag Archipelago depicts the basest depths of human evil, it demonstrates the highest pinnacles of human understanding. The book isn’t just a documentation of evil but an exploration of it. How can such profound evil exist? Writes Solzhenitsyn:

It is permissible to portray evildoers in a story for children, so as to keep the picture simple. But when the greater world literature of the past—Shakespeare, Schiller, Dickens—inflates and inflates images of evildoers of the blackest shades, it seems somewhat farcical and clumsy to our contemporary perception. The trouble lies in the way these classic evildoers are pictured. They recognize themselves as evildoers, and they know their souls are black. …

But no; that’s not the way it is! To do evil a human being must first of all believe what he’s doing is good, or else that it’s a well-considered act in conformity with natural law. Fortunately, it is in the nature of the human being to seek a justification for his actions.

The twentieth century taught us that evil is ideologically agnostic (both roads lead to Rome) — but, argues Solzhenitsyn, evil in its most ruthless form is ideologically dependent.

Macbeth's self-justifications were feeble — and his conscience devoured him. Yes, even Iago was a little lamb, too. The imagination and spiritual strength of Shakespeare's evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses. Because they had no ideology. Ideology — that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others' eyes....

The gulag system didn’t happen overnight, but it took years to build the apparatus of state terror. A civilization succumbs to evil by degrees as its populace surrenders gradually to propaganda, fear, and coercion, and writes Solzhenitsyn, “Every man always has handy a dozen glib little reasons why he is right not to sacrifice himself." At one point, he wonders why he himself kept silent when he was being moved via public transportation to a new jail before his sentencing.

…[B]y a miracle I had suddenly burst out of there and for four days had peeled like a free person among free people, even though my flanks had already lain in rotten stream beside the latrine bucket, my eyes had already beheld beaten-up and sleepless men, my ears had heard the truth, and my mouth had tasted prison gruel. So why did I keep silent? Why, in my last minute out in the open, did I not attempt to enlighten the hoodwinked crowd?

He concludes:

As for me, I kept silent for one further reason: because those Muscovites throning the steps of the escalators were too few for me, too few! Here my cry would be heard by 200 or twice 200, but what about the 200 million? Vaguely, unclearly, I had a vision that someday I would cry out to the 200 million. But for the time being I did not open my mouth, and the escalator dragged me implacably down in the nether world.

The Gulag Archipelago was one of the bestselling books of the twentieth century — the first abridged version sold 30 million copies alone — so Solzhenitsyn's vision turns out to be eerily prescient. His chilling firsthand account alongside the hundreds of testimonies documented in his book served as a persuasive indictment of the Soviet government and shattered the credibility of Marxism. Not only that, it traced the origins of Soviet terror not to Stalin but to Lenin, exposing the brutal means by which he consolidated power and challenging his status as revolutionary hero.

Clearly Solzhenistyn gets a free pass on not yelling out to the world when he had the chance, but, the reader can’t help but wonder, how would the rest of us act when face to face with true oppression? (“Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth.”)

Those who endure the brutalities of the gulag system must eventually dissociate from the flesh either of two ways — by parting with it altogether, or if they’re among the lucky few, by transcending to a spiritual plane of existence. By the grace, it feels, of some higher power, one of these enlightened survivors took it upon himself to show us the path to ignorance and evil so that we could find the path to understanding and decency. As a vital, meticulous primer on the creeping nature of state terror and the incremental way by which men yield to it, The Gulag Archipelago is the ultimate cautionary tale. But more than anything, in its pursuit — and attainment — of Truth, it is an unequaled spiritual work.